Call Us: 855.266.5676 | 954.684.0218

Email Us: info@curtisstokes.net

Call Us: 855.266.5676 | 954.684.0218

Email Us: info@curtisstokes.net

The Automatic Identification System (AIS) is a complex and sophisticated system of marine navigation technologies with several underlying deployment methods. AIS is intended to assist the watchstanding officer responsible for the helm of a vessel. In two principle forms, it is used across the entire range of vessel sizes, from the world’s largest cargo ships to outboard fishing boats and canoes. It is used on the open ocean and in the world’s busiest harbors.

AIS “transponders” are two-way VHF radio devices fit with internal GPS receivers. AIS transponders exchange information about the host vessel, the present voyage and current operations with AIS-equipped land stations and other vessels. Citizens, and certainly boaters familiar with AIS, usually think of AIS as a “Navigation Safety Tool,” which is the purpose for which the technology was originally developed. However, there has emerged since 9/11/2001 a significant interest in AIS by US Homeland Security, federal, state and local policy-making politicians, and many local law enforcement agencies who believe AIS is an appropriate tool to use to track all vessels on US waters. These two uses represent dissimilar, competing interests. Citizens should understand that these interests are not the same, are not mutually compatible with current technologies, and can easily lead to mutually contradictory use and regulation.

In general, Class “A” AIS transponders are designed for the needs of large commercial vessels. Class “B” AIS transponders address a more narrow standard, assumed to be appropriate aboard pleasure craft. Marine VHF Radio channels 87B (161.975Mhz) and 88B (162.025Mhz) are reserved for use by the AIS “system.” These channels broadcast the VHF “Data Link” consisting of many different unique inter-system messages. Class “A” transponders have VHF internal radios that transmit at 12.5 Watts, providing a nominal range of 20 – 25 NM. Class “B” transponders have internal VHF radios that transmit at 2 Watts, providing a nominal range of 7-8 NM.

To avoid “stepping on” each other, the AIS system uses a variety of time sharing technologies, known as a group as “Time Division, Multiple Access” (TDMA). The TDMA specification defines 4500 individual time periods per minute. The total duration of each time slot is 26.5 milli-seconds (ms). TDMA technologies used in the AIS system include:

In units using SOTDMA and RATDMA algorithms, the receiver listens simultaneously to both AIS VHF channels and makes a map of all the time slots on the composite VHF data link (VDL). Some AIS messages are longer than others, and require more than a one single time slot in the VDL. The unit uses the slot map to locate the needed number of adjacent, free times slots in which to send its complete message, and sends its message when that set of slots rolls around. This is ideal for many applications because it does not require reservation of slots by a base station. Thus, the schema is not dependent on base stations (not many base stations in the open ocean). Class “A” shipboard AIS uses SOTDMA. Class “B” AIS uses CSTDMA.

In the TDMA schema, SOTDMA units receive priority in time slot allocation, so Class “A” AIS is guaranteed an assigned time slot. Class “B” CSTDMA units listen for the absence of a signal on the transmit frequency on a slot-by-slot basis. The absence of a signal in any given time slot implies that the time slot is available. If available, any Class “B” CSTDMA unit can “jump in” and transmit its message. However, CSTDMA is a “free-for-all” schema; if only one Class “B” unit transmits during a free time slot, that message will be heard throughout the system. If, however, two or more Class “B” units transmit at the same time, the result is known as a message “collision.” In high traffic density locations, message collisions can result in lost messages. Delivery of Class “B” messages is not guaranteed in the TDMA system schema.

The AIS VHF Data Link (VDL) also supports floating and fixed Aids-to-Navigation (AtoN), such as floating buoys and lighthouses, meteorological and tide level sensors, and satellites carrying AIS. Messages types used for remote monitoring and control of such aids are used to receive and disseminate information about their location and operational availability to ships transiting nearby. AtoNs generally use RATDMA, and are guaranteed time slots in the system. This adds to the message traffic with which Class “B” users must compete.

In the Fall of 2013, the worldwide AIS message structure consisted of 26 different message types, called sentences. The three most common sentence types transmit 1) permanent information describing the host vessel (its name, vessel type, country-of-registry, registry number, etc), 2) dynamic information describing the host vessel’s current voyage (last port-of-call, current operating status, etc) and 3) real-time navigation information about the current operation and status of host vessel (position, speed, direction-of-travel, rate-of-turn, etc).

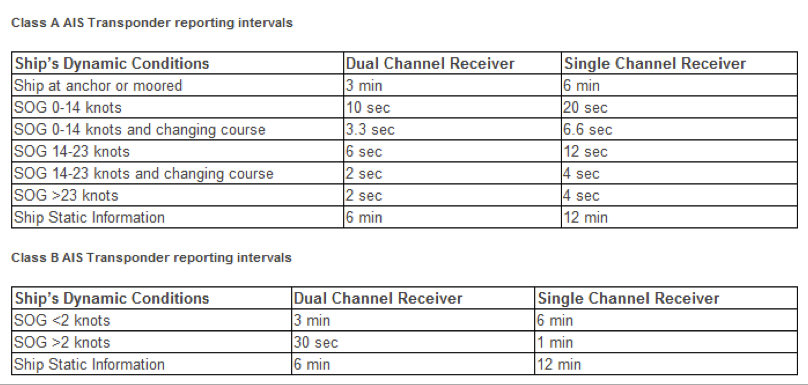

Class “A” transponders transmit navigation and vessel identity information more frequently than their Class “B” counterparts, and also transmit on both VHF channels. Class “B” transponders transmit information at longer-separated intervals, and some Class “B” units transmit on only one of the two AIS VHF channels.

AIS receivers do not transmit information about their host vessel, but they do receive information from other vessels and AtoNs. Receivers and transceivers are available with built in single-channel and dual-channel options. For those interested, detail on AIS message structure (format) and content (data) can be found on the US Coast Guard site, here: http://www.navcen.uscg.gov/?pageName=AISMessages. Significantly more technical detail can be found here: http://gpsd.berlios.de/AIVDM.html#_aivdm_aivdo_sentence_layer.

Only a small percentage of all commercial vessels are actually required by law (IMO Treaty) to carry AIS transponders; large vessels over 300 gross tons, some large tows, and some passenger ships. The US Navy does not use it, which is potentially problematic in all US East and Gulf coast ports, certainly the St. John’s River, FL, the St. Mary’s River, GA, and the southern Chesapeake Bay, VA. The US Coast Guard uses AIS only very selectively, mostly on small patrol and “swift boats,” and not always there. Many tow vessels do not use AIS. Few commercial fishing boats use AIS. The Staten Island Ferry in New York Harbor and many swift ferries in large harbors do not use it. Some ports in the US have adopted port-specific AIS carriage requirements as part of port, maritime facility, vessel and offshore platform security programs. Some fixed “ground facilities” use AIS, such as Vessel Traffic Services (VTS) monitoring stations and other controlled waterways, AtoNs, and SART units. Some orbiting satellites carry AIS tracking equipment. So, AIS deployment and use varies greatly from place-to-place and waterway-to-waterway along the US east coast, the gulf coast and the inland river system, and certainly varies in Canada, the Bahamas, the Caribbean and offshore.

AIS aboard pleasure craft is undeniably a cool toy. It is growing in popularity and mystique, and does provide a means for owners to display their wealth. However, I do not believe that AIS transponders are generally appropriate for wide-spread use aboard pleasure craft. I am not pursuaded that AIS actually assists the pleasure craft “watchstander” achieve “increased safety” in the vast majority of pleasure craft applications. Furthermore, many AIS transponders aboard pleasure craft simply serve to pollute the VHF radio channels (87B, 88B) with unnecessary transmissions, and can wind up intermittently frozen out of the capacity of the TDMA system in busy traffic areas.

A competent captain maintains a continuous and effective visual watch at the helm at all times while under way. This is good seamanship and a requirement of US Coast Guard navigation rules. Electronic position data about other vessels is generally unnecessary to pleasure craft captains who maintain even a cursory visual watch. With an effective visual watch, captains will have many miles of visual and situational awareness of approaching vessels of whatsoever kind, and ample time to plan safe passing courses. This is especially true at sail, trawler and cruiser speeds. In busy harbors, like Annapolis, MD, there are many different boats moving at many different speeds in many different directions at any one time; that is, way too many for the captain to take the time to take eyes off the water to identify and interpret visually on an electronic display of AIS targets. In Maine in heavy fog, we found many sailboats fit with AIS. They had power for their AIS transceivers, but did not answer their VHF radios when called to arrange safe passage. So, something grossly wrong with that picture, and certainly not an effective use of AIS.

Because of the relatively long (30 seconds minimum) update intervals with Class “B” AIS, vessels with Class “B” transponders are almost always not where they are shown to be at a receiving vessel’s chart plotter or electronic display console. Again because of the long update intervals (6 minutes minimum), pleasure craft can be past you before you see the vessel’s name on your chart plotter/electronic visual display. Since the “real estate” on a chart plotter/electronic visual display device can be quite limited, the greater the number of vessels that are transmitting, the more visual “clutter” occurs among the many targets presented to the operator if the receiving display. Much time and attention is required of the operator to absorb and interpret the clutter. The usefulness of a proximity monitor is dramatically reduced. Inevitably, the operator spends less time with “eyes on the water,” where they should be in order to “maintain a proper visual lookout.” And of course, of the total number of pleasure craft running around on a sunny summer afternoon in Annapolis, today, only a small minority (thankfully) have AIS anyway. The net is, especially in the hands of captains who do not understand the limits of the technology, the tool can create over-confidence and a false sense of security. The tool can be more of a distraction than an aid!

For pleasure craft owners/operators, there are also potential personal security “downsides” with AIS. A vessel anchored in a remote location while transmitting position information is advertising their position to anyone with an AIS receiver, including several free smartphone apps. That information could certainly be of interest to persons with nefarious intent. Furthermore, do not assume that a pleasure craft using a Class “B” AIS transponder will necessarily be seen on the Electronic Chart and Display Information System (ECDIS) aboard the bridge of a commercial ship. The software aboard some commercial vessels can be set to suppress the display of Class “B” transponders in order to allow the watchstanding officer to focus on other large, Class “A,” targets and commercial traffic. And anyway, commercial vessels in charted sea lanes and formal Traffic Separation Zones will not divert their course for pleasure craft. It is the responsibility of pleasure craft to avoid large ships.

Given the above as “general observations,” I do assert that pleasure craft used as long range cruisers can definitely benefit in some situations from having an AIS transponder in operation aboard. For those applications, I recommend Class “A” rather than Class “B” AIS units. I also recommend a transponder that supports the “quiet mode”/”silence” function. Transponders operating in quiet mode do not transmit data; they act as receive-only devices. In “quiet” mode, they do not routinely contribute to VHF pollution, do not compete for TDMA time slots, and do not result in the unnecessary distraction of other waterway users. For routine, day-to-day operations in visual conditions, I recommend using the transponder as a receiver, in “quiet” mode. I suggest captain’s treat the use of the “transmit” mode as an exceptional situation, reserved for use:

These above are, after all, the situations where use of the tool may actually increase safety.

Vessels required by law to carry AIS are required to leave them on 24x7x365, even when at anchor or tied up in port. There are no pleasure craft required to carry AIS, so there is never a time when pleasure craft are required to leave AIS units transmitting when secured in a slip in a marina. It’s poor courtesy and bad seamanship to do so. We therefore ask, please, turn transponders to “quiet mode,” or “off,” when the boat is secured in a slip in a marina! A boat in a slip in a marina is not a navigation hazard to anyone or anything. An AIS transponder on such a vessel is just a VHF polluter.

For pleasure craft generally, our recommendation continues to be to fitup a dual-channel AIS receiver. Sanctuary is fit with an ICOM® MXA-5000™ dual-channel AIS Receiver. The AIS receiver shares an antenna with our back-up ICOM® IC-M504™ Marine VHF radio. The ICOM® receiver has a built-in transmit/receive relay. We are very happy with this arrangement.

By Jim Healy from his Blog Travels of the Monk 36 Trawler, Sanctuary

Disclaimer: Curtis Stokes and Associates does not necessarily agree or promote the content by the above author. This content is to be used only with the reader’s discretion.

© 2024 Curtis Stokes & Associates, Inc. | All rights reserved.